Whose Peace? The Elusive Quest for Stability in South Sudan

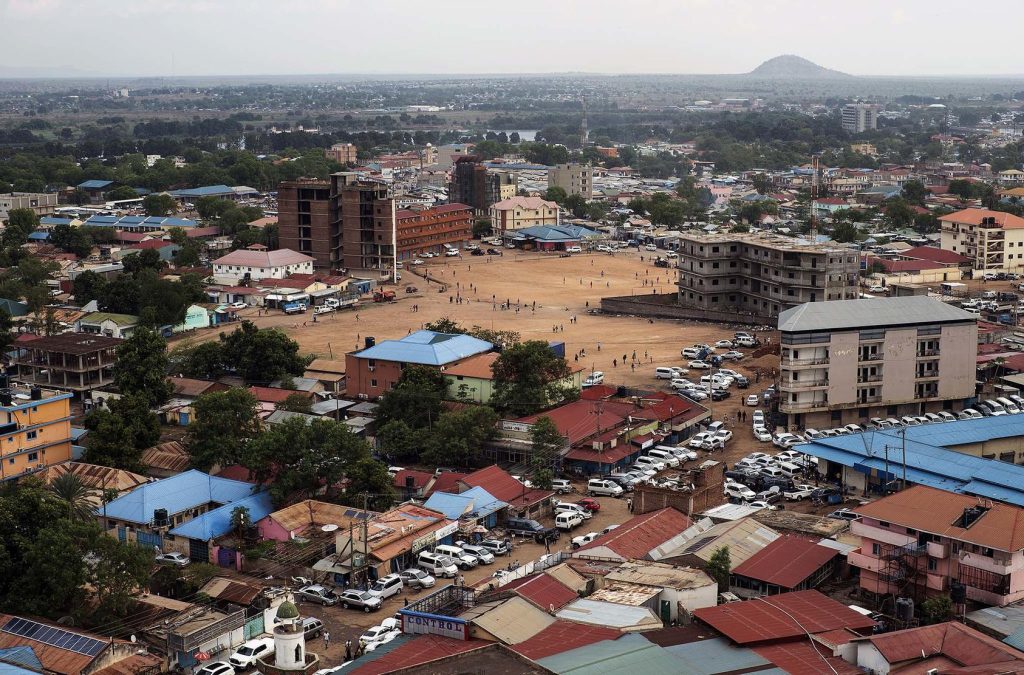

An overview of South Sudan's capital city, Juba, on March 21, 2018. South Sudan, the world's youngest nation, is in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. (Kassie Bracken/The New York Times)

South Sudan, the world’s youngest nation, celebrated its hard-won independence in 2011 with widespread jubilation. The culmination of decades of struggle—from the Anyanya I movement in the 1950s and 60s through to the comprehensive peace agreements of the early 2000s—was heralded as the dawn of a new era. Yet, as the dust settled, the hoped-for peace has proven heartbreakingly elusive. The people of South Sudan now find themselves questioning: whose peace are we truly striving for?

South Sudan’s independence was the result of a protracted struggle that saw immense sacrifices. The Anyanya I rebellion, which lasted from 1955 to 1972, was the first major conflict aimed at addressing the marginalization of the southern region by the northern-dominated Sudanese government. This conflict set the stage for future uprisings and negotiations, culminating in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). The CPA, brokered with significant international support, was a landmark accord that paved the way for the 2011 referendum and the eventual independence of South Sudan.

The birth of the nation was met with hope and international goodwill. However, the underlying tensions and unresolved issues from decades of conflict soon resurfaced. The euphoria of independence quickly gave way to internal strife, leading to a brutal civil war in December 2013. This conflict, primarily between forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and those aligned with his former deputy Riek Machar, has caused immense suffering, displacing millions and resulting in countless deaths.

The cyclical nature of conflict in South Sudan raises a critical question: whose peace are we seeking? The people, who bear the brunt of violence and displacement, desire a stable and prosperous nation. Their definition of peace is rooted in safety, access to basic needs, and opportunities for a better future. Conversely, the peace often pursued by political leaders appears more focused on power consolidation and maintaining a fragile status quo that benefits a select few.

This dichotomy is starkly illustrated by the numerous peace accords that have been signed only to be broken. The 2015 Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) is one such example. Despite high hopes, the agreement quickly unraveled, leading to renewed fighting. The revitalized peace agreement in 2018 also shows signs of strain, with sporadic violence and political bickering continuing to undermine its implementation.

The recurrent breakdown of these peace agreements suggests that the interests of the leaders often diverge significantly from those of the general populace. For many leaders, peace is a strategic tool used to gain legitimacy, secure international funding, and maintain control over the country’s vast natural resources, particularly oil. For the average South Sudanese citizen, however, peace is a matter of survival and a prerequisite for economic and social development.

A troubling pattern emerges when examining the timing of peace talks and initiatives. Efforts like the Tumaini Peace Initiative, led by regional actors including Kenya, often gain momentum as elections approach. This raises suspicions that such initiatives are driven more by political expediency than genuine efforts to achieve lasting peace. The pattern suggests that leaders may use peace talks to bolster their political legitimacy and appease international observers, rather than addressing the root causes of conflict.

The upcoming elections are no exception. As the nation braces for another round of voting, peace initiatives are once again in the spotlight. However, the true test will be whether these efforts translate into tangible improvements in the lives of ordinary South Sudanese people, or if they merely serve as a veneer to placate external pressures.

The timing of the Tumaini Peace Initiative, which coincides with the lead-up to the elections, adds to the skepticism. Critics argue that the initiative, while commendable in its goals, is being leveraged by political elites to create a façade of stability. The leaders appear to be more focused on securing their positions of power rather than genuinely working towards a sustainable peace that benefits all citizens.

The human cost of South Sudan’s ongoing conflicts cannot be overstated. Since the outbreak of the civil war in 2013, millions have been displaced internally and across borders. The United Nations estimates that over 4 million people have fled their homes, with about 2.2 million seeking refuge in neighboring countries such as Uganda, Sudan, and Ethiopia. This mass displacement has created one of the largest refugee crises in Africa, putting immense pressure on already strained resources in host countries.

Internally, the conflict has led to widespread food insecurity and a humanitarian crisis. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports that over 7 million people, more than half of the country’s population, are in need of humanitarian assistance. Malnutrition rates, especially among children, are alarmingly high. The persistent violence has disrupted agriculture and livelihoods, leading to chronic food shortages and heightened vulnerability to famine.

The impact on children and women has been particularly severe. Many children have been orphaned or separated from their families due to the violence. The education system is in disarray, with many schools destroyed or repurposed as shelters. Women and girls face heightened risks of gender-based violence, including rape and abduction. The ongoing instability has eroded traditional social structures, leaving many without the support systems they once relied on.

The international community and regional actors have played pivotal roles in South Sudan’s peace process. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), comprising East African nations, has been instrumental in mediating peace talks. The African Union, the United Nations, and key international players like the United States and the European Union have also been heavily involved in peacekeeping and humanitarian efforts.

Despite these efforts, the peace process has been marred by setbacks and frustrations. The UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) has faced challenges in protecting civilians and facilitating peace. Allegations of bias and ineffectiveness have sometimes undermined the credibility of international interventions. Furthermore, regional dynamics, such as the interests of neighboring countries in South Sudan’s oil wealth, have complicated the peace efforts.

Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda have all played roles in hosting peace talks and refugees, but their involvement is not purely altruistic. These nations have strategic interests in South Sudan’s stability, ranging from economic investments to regional security concerns. Balancing these interests with the genuine needs of the South Sudanese people has proven to be a delicate and complex task.

For peace to be meaningful and lasting in South Sudan, it must transcend the narrow interests of political elites. It requires a concerted effort to address the underlying issues that fuel conflict: ethnic divisions, economic disparities, and weak governance structures. International actors and regional partners must hold South Sudanese leaders accountable, ensuring that peace agreements are not just signed but fully implemented.

Moreover, there must be a renewed focus on grassroots initiatives that empower communities and promote reconciliation. Peace must be built from the ground up, with the active participation of civil society, women, and youth who have been disproportionately affected by the violence.

One promising approach is the inclusion of traditional conflict resolution mechanisms. South Sudan has a rich cultural heritage of local governance and conflict resolution practices that, if leveraged appropriately, can complement formal peace processes. Engaging local leaders and communities in dialogue and reconciliation efforts can help build trust and foster a sense of ownership over the peace process.

The quest for peace in South Sudan is fraught with challenges, but it remains an imperative. The question of whose peace we are seeking must be answered with a clear and unequivocal commitment to the people of South Sudan. Only by prioritizing their needs and aspirations can the nation hope to break free from the cycle of conflict and build a future worthy of the sacrifices made for its independence.

As the international community and regional actors continue to support South Sudan, they must ensure that their efforts are aligned with the genuine desires of the South Sudanese people. This means moving beyond superficial peace initiatives timed to coincide with election cycles and focusing on long term, sustainable solutions. It means holding leaders accountable and ensuring that the voices of the marginalized and the displaced are heard and acted upon.

Ultimately, the peace that South Sudan needs is one that is inclusive, just, and enduring. It is a peace that addresses the root causes of conflict and lays the groundwork for a stable and prosperous future. It is the peace that the people of South Sudan have long yearned for and richly deserve.